Many confuse Memorial Day with honoring our living veterans and currently serving servicemen and women. That’s Veterans Day. Memorial Day is about remembering and honoring those who served our country that have passed on, especially those who died while serving on active duty.

I’m a veteran who, as a professional writer and publisher, has dealt in the memories and stories of other veterans. Making sure they do not fade with time and become lost and forgotten. I’ve spoken, worked, and spent time with many of our most decorated veterans from World War II, the Korean and Vietnam wars, the Cold War, and the 21st-century War on Terror. They want to get down the What, Where, and When of life-shaping events in their lives… and often the Why. And every day—not just on Memorial Day—they want to honor those they served with who have died. Their stories achieved their purpose and deepened my appreciation for the holiday.

My friend, Jim Zumwalt, shared a perhaps apocryphal story in his book Bare Feet Iron Will | Stories from the Other Side of Vietnam’s Battlefields. In late 1968, a memorial chapel was destroyed during a Viet Cong mortar attack against Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Saigon, Vietnam. As a chaplain passed by its ruins a few days later, his eye caught the edge of an object among the rubble. He pulled it out to find a board upon which was inscribed writing of unknown origin:

Not for fame or reward,

Not for place or rank,

Not lured by ambition

or goaded by necessity,

But in simple obedience,

as they understood it.

These men suffered all,

dared all and died.

Lest we forget… lest we forget…

So, in the rubble was found something that admonishes us. Destruction and death—especially witnessed firsthand—sober and alter us. Perhaps that gives the words greater import. It makes us pause and reflect on our mortality and appreciate what we still have that others have lost. We have few ruins in the United States that evoke similar thoughts. But there are many buildings and monuments that should make us grateful for those the structure honors and value their sacrifice. The best and most lasting are those erected on firm ground, resolutely attached to a bedrock foundation beneath, stable, and able to bear great loads, withstanding wind or storm. Societies and nations are built the same way. But not with bricks and mortar. A country is made of the character of its people, manifested in its history, traditions, and the principles it espouses. Some individuals contribute more to that history—often becoming the sum and substance of a nation’s foundation—so that the ‘center does hold.’ Like mortar and stone, their blood and bone—their grit and determination—connect us.

Over two-plus centuries, our land has become dotted with remembrances in stone. Of the men and women who wore our nation’s military uniform, swearing an oath to protect and defend all we hold dear. The cloth they wore is the fabric of hopes and dreams of the past, present, and future. And many died so young… so very, very young.

“We have shared the incommunicable experience of war. We have felt, we still feel, the passion of life to its top… In our youth, our hearts were touched with fire.”—Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. (who served as a young Union soldier in our Civil War)

At Valley Forge (not a battle but a turning point in our country’s history), the Continental Army was bloodied and beaten, ready to quit… but didn’t. At Gettysburg, the Meuse-Argonne, Guadalcanal, the Battle off Samar, Leyte Gulf, Bastogne, the Battle of Chosin Reservoir, Getlin’s Corner, Khe Sanh, in the USS STARK and USS COLE, Baghdad, Fallujah, Kandahar and many other places—domestic and foreign—known and regrettably unknown, they served and died.

Their gravestones, monuments, memorials, the markers of their death, and the placards above their resting place forever call for us to remember them. Above all, these men and women should be honored this Memorial Day. No matter where they rest, they are forever rooted deeply in our nation’s bedrock—in its stone.

“They shall not grow old, as we that are left grow old.

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.”

—Laurence Binyon, ‘For the Fallen’ (1914)

just before the slaughter on the Western Front in WWI.

General Richard ‘Butch’ Neal, USMC (Ret.), used the following as a dedication epigraph in his memoir What Now, Lieutenant? Leadership Forged from Events in Vietnam, Desert Storm, and Beyond:

“From this day to the ending of the world,

We in it shall be remembered,

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother….”

—William Shakespeare

Brothers. I want to tell you about one, my friend Jim Zumwalt’s. Because not all our heroes… not all of those we should honor… die on the battlefield. Some survive and die after a full measure of life. Others come home wounded and injured and are ill-destined to fall too soon and far from where fate has placed a finger upon them. Upon commissioning in 1968, Jim’s brother, Elmo R. Zumwalt III, attended the Navy Communications Course in Newport, Rhode Island, and later reported to USS Claude B. Ricketts (DDG-5) in Norfolk as the Electronics Officer. In 1969, he volunteered to serve as a swift boat commander, one of the most dangerous assignments in Vietnam. Lieutenant JG Zumwalt took command of Swift Boat PCF-35 and, during his tour, was awarded two Bronze Stars for heroic conduct. He and his crew also received the Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry for their heroism in Cambodia. Jim’s brother did—for a while—survive the war. Elmo died in August 1988 from cancer believed caused by exposure to Agent Orange. The U.S. Armed Forces in Vietnam used the defoliant and sprayed continually along the rivers he and his crew patrolled. The very thing meant to help him and his men ultimately led to his death.

The often mortal—or life-shattering—wounds of war… of service to our country are not always seen, but they are there, and we must recognize and honor those who suffered them.

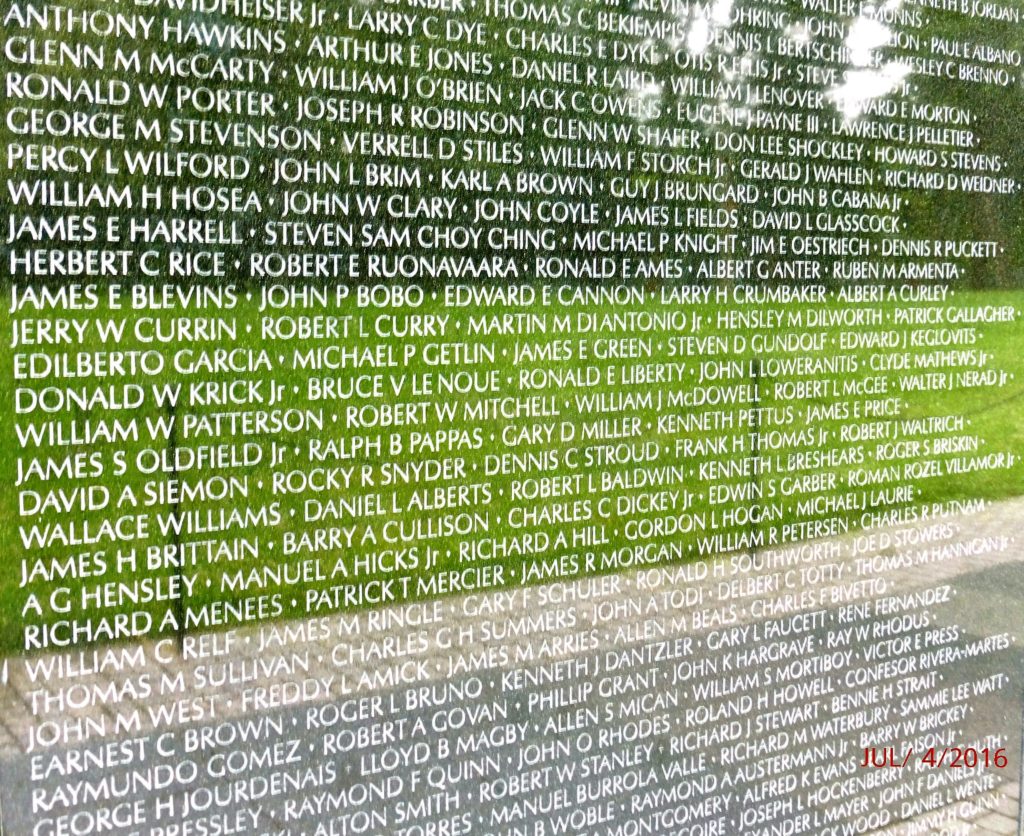

I’ll share a brief vignette from Butch Neal that’s a fitting close to this perspective on Memorial Day. He told me about a chance meeting at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial as we were finishing work on his book. I knew we had to add to his story when I heard it. The Marine mentioned in it—*John Bobo, a 24-year-old posthumous Medal of Honor recipient—died providing defensive fire for his men after his leg was blown off in a battle that pitted a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) battalion of 700+ men against the approximately 150 men of Company I, Third Battalion, Ninth Marines, Third Marine Division. Only three of the seven officers in the field at the beginning of that battle walked out. Butch was one of them and afterward was awarded his first Silver Star. Here’s what he told me (that became the PostScript to end his book):

Recently, as was my custom, I stopped at the Vietnam Wall to see the names and think for a few minutes about my Brothers. As I stood in front of Panel 17E, looking at the fifteen names all clustered around row 70, a little elderly lady (a grandmother type, my age) moved almost in front of me. I was about to step back to give her more room when I realized she was one of the volunteers who helped people at the Wall find names, learn the history, etc. She was polite and said she was looking for row 70. I pointed it out to her and asked. “What name are you looking for?”

“John Bobo.” Her eyes hadn’t stopped scanning the names.

I almost fell over. I pointed to his name.

“Thank you. I’m doing a pencil etching of his name. Someone requested it on our website,” she said.

Talk about a coincidence, it’s a small world, whatever, but it was an amazing happenstance. “John was a Medal of Honor recipient,” I told her. She immediately checked her list, nodding her head when she saw that was so. “Thank you for what you’re doing,” I told her, then turned away to continue my walk, happy although it was cold, raining, and the cherry blossoms had not yet exploded. There were those—other than me—who would not let my Brothers be forgotten.

—Butch Neal

This Memorial Day, please take a moment to pay respect to—and remember—all who served like John Bobo and Elmo R. Zumwalt III and have made the ultimate sacrifice in service to our country.

*Medal of Honor Citation:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as Weapons Platoon Commander, Company I, Third Battalion, Ninth Marines, Third Marine Division, in Quang Tri Province, Republic of Vietnam, on 30 March 1967. Company I was establishing night ambush sites when the command group was attacked by a reinforced North Vietnamese company supported by heavy automatic weapons and mortar fire. Lieutenant Bobo immediately organized a hasty defense and moved from position to position encouraging the outnumbered Marines despite the murderous enemy fire. Recovering a rocket launcher from among the friendly casualties, he organized a new launcher team and directed its fire into the enemy machine gun position. When an exploding enemy mortar round severed Lieutenant Bobo’s right leg below the knee, he refused to be evacuated and insisted upon being placed in a firing position to cover the movement of the command group to a better location. With a web belt around his leg serving as tourniquet and with his leg jammed into the dirt to curtail the bleeding, he remained in this position and delivered devastating fire into the ranks of the enemy attempting to overrun the Marines. Lieutenant Bobo was mortally wounded while firing his weapon into the main point of the enemy attack but his valiant spirit inspired his men to heroic efforts, and his tenacious stand enabled the command group to gain a protective position where it repulsed the enemy onslaught. Lieutenant Bobo’s superb leadership, dauntless courage, and bold initiative reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the Marine Corps and the United States Naval Service. He gallantly gave his life for his country.