![What The Wind Blew Away [Fiction] What The Wind Blew Away [Fiction]](https://adducentcreative.com/wp-content/uploads/What-the-Wind-Blew-Away-2024-Short-Fiction-By-Dennis-Lowery-2-768x1226.jpg)

For the past month, Samantha’s grandfather had sat on the front porch each day as the summer deepened into a scorched August, whose heat often lasted into the first weeks of September. His face had drawn tighter each day as the grass and weeds grew tall and wild around the tree, crowning the crest of the hill. Samantha knew about the tree and what it meant to him. She hated it.

That morning she had seen the—about to do something you’d rather not but must—expression on her grandfather’s face. She thought of the same one her mother used to get as the ‘time-to-clean-the-cat-litter-box’ look. When she’d grown older and her mom had passed the chore to her, Samantha had understood. Her grandpa had come inside, sighed deeply, crossed the room, and got his broad-brimmed hat from the peg by the kitchen door to the backyard. He set the cap on his head and stepped outside without a word. From the window over the sink, she saw him enter the barn. In a few minutes, she had heard its starting cough, and the chuff and chug of the Massey-Ferguson’s engine got louder as the tractor approached the house and less so as it moved toward the hill.

Samantha went out onto the front porch to watch him. She cursed the sun’s blistering brightness with a sideways scowl beneath her headscarf. She hated it most of all.

As the tractor huffed along—spitting through the vertical exhaust pipe her grandfather always warned her not to touch—it grew even louder as the sound echoed off the hillside. Grandpa headed up in a straight line and would work his way around the tree and outward in an expanding concentric circle. As he closed on the top of the hill, the sun focused all its rays. This side of the knoll where the clump of rocks created an overhang showed a sliver of shadow as the sun arced over to fall full force on Grandpa.

“Samantha.”

She turned as her grandmother came out onto the porch. Dangling by the plastic loop connecting them, in one hand, she held two bottles already sweating with condensation. “Run these up to your papaw and make sure he drinks them.”

Samantha peeked again from beneath the edge of the porch’s shade at a sky, so piercing blue her eyes ached.

Her grandmother studied her for a moment, measuring her reluctance. “Please, honey.”

Her grandma couldn’t climb the hill. “Okay, Mamaw,” she took the bottles of water, Grandpa’s favorite flavor Kiwi-Strawberry, and set them on the porch rail. The long sleeves of her white shirt now rolled down; she picked up the umbrella always with her outside during the day.

The gray-haired woman surveyed Samantha’s preparations, and a growing sadness tightened her face. Her granddaughter had lost more than her mother. She was losing—to bitterness and fear—the joy she could still find in the simple moments of growing up and the pleasure and beauty in the world.

Samantha scrutinized the hill, haloed by the haze of dry-summer dust settling in the still air. Younger, she had begged her mom to carry her up there when her little legs couldn’t make the climb. A little older, and she’d made it holding her hand. As she grew up, it became a mother-versus-daughter race to the top. There they’d have picnics under the sun and in the semi-shade of the tree. Her mom would pick thistles blowing on them to make their tiny stalks float and dance in the air. “Make a wish Samantha,” she would tell her. Sometimes the wind carried them out of sight. She always wanted to ask her mom what happened to those wishes—the ones that sailed away—but never remembered. Now it was too late. She’d never know her mother’s answer.

Samantha popped the umbrella open, picked up the water bottles by the loop, and stepped off the porch and under the sun. Entering the field through the gate, her dragging steps scuffed up puffs from the dried grass clippings left by grandfather’s bush hog. The mower attachment his tractor towed to cut field and pasture grass. Ten minutes later, already drenched in sweat, she reached the base of the hill. With the umbrella angled to cover her, she climbed for another ten minutes to the top. Papaw waved as she approached. He had cleared the area around the tree and gestured for her to follow him as he turned toward it. He lowered the brush hog at the edge of the tree’s shade and shut off the tractor. In the silence, there wasn’t a whisper of wind.

The summer had been hotter than any she could remember. She still smelled the creosote of the asphalt—a stench she forever associated with her mother’s death—in the hospital parking lot. The heat had leached upward through the bottoms of her shoes and climbed her legs like the mercury in the thermometer Grandpa had put on a post by the porch. Then would reverse once she stepped into the over-air-conditioned hospital to sit with her mother, growing colder as she lay dying.

She glared at the underside of the black umbrella through the sting of sweat in her eyes, the pull of the headscarf’s edges sticking to her brow. She held the sides of the bottles against a cheek, a temporary relief. Her grandfather wiped his face with a handkerchief when she reached the tractor. He took off his hat and mopped his bald head.

“Here you go, Papaw,” she handed him the water. He stripped one bottle from the loop, unscrewed the top, drank, and smacked his lips. He gave it back and stuck the second bottle into his pants unbuttoned right cargo pocket. She took a drink as he rolled his sleeves up. The hair on his arms—so thick she always wondered what happened to the hair on his head—was matted with sweat.

“Hot one today,” he grunted as he slid off the seat and straightened. Both hands pressed at the small of his back as he pushed himself erect. “I need a breather.” He smiled, patted her shoulder, and walked to the tree’s base. He thumped the thick trunk with the palm of his left hand. “I planted this when your Mamaw told me she was pregnant with your momma,” he stroked the rough bark. “This was our—mine and your mom’s—tree.”

She didn’t want to listen to the story again. “Papaw,” she touched his arm. It wasn’t just sweat on her cheeks.

“Okay, honey.” He lowered to the ground with his back against the tree he had seen grow up with his daughter and wiped his eyes, rubbing at the corners with his thumbs. Samantha sat next to him. After a minute, her head was on his shoulder. He turned and rested his chin on her. “But your mother loved this tree… this hill.”

“I hate this place.”

He knew she didn’t. What she hated was the hurt of being here without her mom, at becoming a teenage girl—facing life—without her mother. He hated that, too; his remaining years spent without his daughter, Annie. Nothing could fill the void; he’d never recover from losing her. But he had to say something, had to help his granddaughter grasp something positive—something meaningful—from their loss.

He studied the frayed ends and tight knots of the rope around the thickest limb overhead. He had pruned away the smaller, lower limbs so the tire swing would have clearance. The tree hadn’t been big enough for Annie—she grew up as it did—but by the time Samantha was born, it was sturdy enough. She had swung, kicking chubby, baby-fat legs, and laughed. “Push me higher!” Samantha had told Annie as he and Helen had videoed them. One of those moments when still new grandparents are about to burst with love for their child and grandchild.

Last summer, he had taken the tire down to replace the ropes. Then Annie got sick, and he and Helen went to her and Sammy in the city to tend to things. He never got around to it. That summer began the last of many things for his daughter… with his daughter. He tilted his head to one side and squinted at his granddaughter. Samantha clutched the rolled-up umbrella to her chest. Her legs were pulled in tight under the shade of the tree as if the sun’s touch was poison. He and Helen had talked to her about the melanoma that had killed her mother. Then the sadness of her mother’s death hardened into a layer of hate against the cause.

A hint of a breeze teased them. The smaller branches above swayed. “Feels good, right?” Samantha turned her face up to him and nodded. The dust the tractor had kicked up had settled on her hot cheeks, and the fresh tears had created tracks. She lowered her head and stretched her right leg to half kick at a clump of thistles too close to the tree to mow with the bush hog. Dislodged, the stems caught the wind and twirled away.

“Papaw, what about the ones floating off? You don’t see them coming down….”

“What do you mean, Sammy?”

“Mom always told me to pick one, make a wish, and blow. And you had to hold the wish in your thoughts until the thistle landed.” She sat up and spun on her rump to face him as she drew her knees up and wrapped her arms around them. “What happens to those wishes? The ones that blow away?”

He rubbed his nose and shifted his legs. He had told that folktale to Sammy’s mother when she was a child, but Annie had never asked that question. “Well, those wishes land somewhere. Wherever the wind takes them, and they carry seeds that can take root, and there, in that spot, they can grow more.” He brushed her chin with his fingertips. “So little girls and boys can find them to wish upon.”

“So, they’re not gone, not lost?”

He twisted the top off the second bottle, took a drink, and passed it to Samantha. “Have some.” She preferred the black-cherry flavor but drank and swallowed, wiping her mouth with the back of her hand. She handed the water back, and he spun on the cap. “No, they’re not gone. Things in life move on, but the important part of them stays with you. That doesn’t change… if you decide to hold them tight. In a way, that’s called faith.”

“Are memories like that? I mean… we can only see them in our minds. But we still feel them.” She paused. The wind had picked up, and he almost didn’t catch what she added. “Like mom.”

“Yes, honey, memories are like that. But we should only keep and cherish the good ones like of your mother.” He paused; the damned sweat was in his eyes. Kerchief out again, he tilted his head back to wipe them and his brow, then folded the sodden cloth to stick back in his pocket. “Your mom’s still with us. She touched so many people’s hearts, and the memories of her are what we hold close.” He looked into his granddaughter’s eyes, so much like Annie’s. “The wind doesn’t always blow things away from us, Sammy. And what does isn’t what’s important. What remains is.”

“God damn melanoma. Goddamned cancer,” she spat.

He agreed. “Shhhh, sweetie, don’t curse. Your Mamaw will kick my butt if she hears you.” His knees told him he had sat too long as he used one hand to push up and steadied himself with the other on the tree trunk. He had brought up a handful of grass and earth in his fist and sifted through his hands. “Too dry,” he brushed a piece of bark from the tree, and it crumbled into powder. “Worst in decades,” he muttered as he rubbed a drooping leaf between thumb and forefinger. Brittle. He worried he’d lose the tree too and considered what to do to run an irrigation line up the hill.

“Papaw?” she waited a moment and tugged his pants leg. “Grandpa.”

He felt the pull as he put his hat on, squaring to sit above his eyes, and glanced down at her. “Yes, Sammy?”

“Why today?”

Thumbs in two belt loops, he hitched up his pants. “What, honey?” He reached down and held out a still strong, sinewy hand to help her stand.

“We don’t come up here anymore,” she pointed up at the tree. “Why today? When it’s so hot.”

He studied her face, framed by the scarf, the red hair, and a dusting of freckles. Her eyes when she stood were not far below his. He realized Samantha would be a tall woman like her mother, his Annie. “We lose things. Sometimes small stuff. Little things that aren’t too valuable we don’t miss. But sometimes,” he paused and thumbed the corners of his eyes again. Damned sweat, he thought. “Bad shit happens—don’t say that word, remember Mamaw—to something or someone important to us. It gets damaged, or they get hurt. They break down or get sick. Sometimes we can’t fix things or them. One day they’re gone, and some we can never replace.” He rubbed the tree’s trunk again and glanced up through the leaves. “Because they were the only ones you….” He blinked, coughed, and thumb-spun the lid off the bottle. Offering to her, she shook her head, and he drank the last. He crumpled and placed it with the cap in the cargo pocket of his pants. “They were the only one of them you’ll ever have.” He put his hands on her shoulders, “We honor what we’ve lost by taking care of what we still have,” he patted the tree again. “I see this tree, and I think of your mother.”

Samantha turned her head. “It makes me sad.”

He stood still, waited for her to look at him, and then continued. “This morning, I remembered what makes me happy and not what makes me unhappy.” He scanned around them and turned back to her. “Your mother loved this hill, this tree, and I have to care for it no matter how miserable I am. And now I’m here again, remembering the echoes of her laughter and the beauty of her smile.” He closed his eyes and sang, “In this place, full of empty space. Her soft and tender love will always shine for me.” The song trailed off as he gazed at the tree’s canopy above them, its leaves moving with the wind. He squeezed his granddaughter’s shoulders and walked toward the tractor.

Samantha thought Grandma will be happy when I tell her he’s singing again. He hadn’t done that since he sang to her mom in the hospital. She bent and plucked something from the grass, held it to her lips, and blew. The wind caught the stalks before they drifted to the ground. And bounced them up to form a line like connected train cars pulling away from them on a current of air. Before they were out of sight, she whispered, “I love you, Mom. I’ll never forget you.”

She turned to follow her grandfather. Now in the tractor’s seat, left-handed, he twisted the key and pressed the starter button. He reached down right-handed to lift the lever to raise the bush hog. As she climbed on the fender next to him, a gust of wind caught her scarf, lifting its loose twining to whirl into the sky. The umbrella unfurled and pulled from her grip, billowing open to sail high, tumbling and spinning over the hill, dancing along with her headscarf away from them in the same direction as the thistles. They watched until they, too, were gone. She squinted up at the glaring sun. He took his hat off and plunked on her head. “Here you go, kid.”

They bounced downhill, the tractor jarring on patches of uneven ground. Still thinking about what Grandpa had said, Samantha glanced over her shoulder at the tree as it got higher and smaller. She took the hat from her head and leaned over to shout so he could hear over the engine noise, “Papaw…” She put the cap on his head, careful not to pull too low over his eyes. “You need this more than me!” She leaned in again to kiss him on the cheek, and he held her with one arm, the other gripping the steering wheel. The clean wind steadied and took away the sting and ache.

He pointed up at the line of clouds bunching ahead and above. They were dense, dark, and charging on the wind toward them. “Breathe, Sammy,” he smiled, “and see what the wind’s bringing us.”

She saw the wrinkled furrows on his forehead smooth as the scudding clouds blocked the sun and cooled the sky. The wind swirled, casting the first drops. Something pirouetted before her nose, and she caught it in cupped hands and peeked inside. An intact thistle. Thinking more about what her papaw had just told her, she grinned into the wind. “Thanks, Mom!”

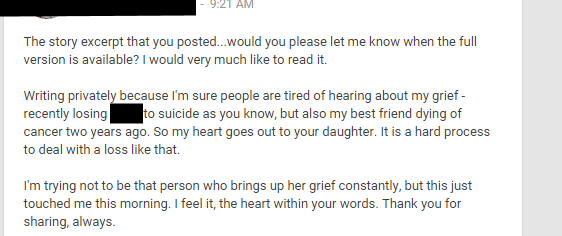

As a writer, you believe what you’re creating will touch someone in some way. But you send your creation out into an often silent world. Maybe it’s just not found so it can be read. After all, we live in a world where we’re inundated with information, social media shares, and posts. Pictures of cute dogs… cute cats… cute girls… and bacon. In all of that, sometimes your writing gets missed. BUT then there are times when you get a message from a reader like this. And it confirms that what you’re doing does reach some people and that it’s touched their hearts. I received this message–screen-grab below–from a reader of the excerpt from this story that I posted.

So, I posted the full story (above).

Note from Dennis

Good stories transport the reader and carry messages that resonate. They’re a compelling way to illustrate the arc of emotions we feel and maybe even come to grips with our own.

Creation in art, music, and literature is often attributed to a muse. A familiar spirit that guides and maybe even sits on a shoulder. One day, while helping select photos for a family album, I went through my oldest daughter’s wedding pictures. One of her best friends, battling cancer and gutting it out though sick, was a bridesmaid. In the weeks following the wedding, she had setbacks. The cancer had spread. And we lost Ashley. She was a brave and bright soul. As I looked at pictures of Ashley at the wedding, I recalled how hard she hugged me after my toast to the new bride and groom… and thought about our loss. And how we heal. Ashley was on my shoulder as I wrote this short story to explain how those we love are never truly gone when they pass on. The vital part of them stays with us. Forever.

Side note: The line that Samantha’s grandfather sings is from the song, ‘In This Place’ by Robin Trower in 1974.

Here are some of the reader comments:

“Great story–and very timely. I lost one of my Marine buddies this week.” –Jim Zumwalt

“Loved it. I felt like I was there…I could smell the mown grass and feel the sting of the glaring sun. I could relate to Sammy’s anger and sadness and when I read those familiar lyrics that her grandpa sang…I was hooked. It was very touching Dennis. Thank you for the thoughtful take on how we keep memories of our loved ones near and dear. The title is beautiful.” -Bobbie T.

“Superbly written.” –Gwendolyn M.

“Wow, what a bittersweet yet beautiful story of love and loss and healing… Thank you for such a poignant and touching story!” -Lisa Wolfington

“Loved your story. It made me think of loved ones that are no longer here. They will always be with me. Thank you.” -Marsha Mooneyhan

“Beautifully written, Dennis.” -Michael Koontz

“A beautiful story of loss and healing; so touching and lovely.” -Nina Anthonijsz

“Talk about tugging at the heartstrings.” -Vicki Tyley

“I love your story; it’s a touching and poignant piece.” -RC de Winter

“Left me speechless and filled with precious memories from when Mom was around. Thank you for this beautiful story.” -L. Moncivaiz

“Thank you, so much. It’s a beautiful story; a sweet and touching read. I need to explore that connection [in the story] I am glad you wrote this as it’s nudging me to explore what it is.” –AD